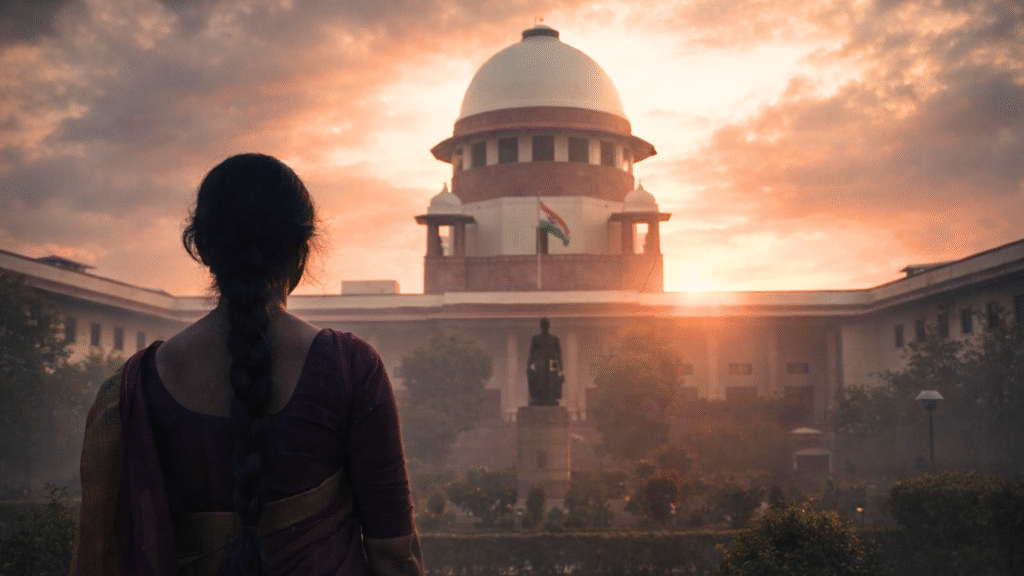

In India, the world’s largest democracy, few institutions have reshaped the landscape of gender equality, LGBTQ rights, and sex crime jurisprudence as dramatically as the Supreme Court. From decriminalising homosexuality and recognising transgender identity to outlawing instant triple talaq and expanding abortion access for unmarried women, the Court has repeatedly placed constitutional morality above social conservatism. In a country where debates over sexuality, religion, patriarchy and personal liberty remain intensely contested, the Supreme Court of India has emerged as an unlikely engine of progressive reform—sometimes ahead of Parliament, sometimes restrained by it, but always central to the fight over who counts as an equal citizen.

The modern arc arguably begins in 1997, with Vishaka v State of Rajasthan. At a time when India had no specific law against sexual harassment at the workplace, the Court responded to the gang rape of a grassroots worker by laying down binding guidelines to prevent harassment. It did something remarkable: it treated international conventions on women’s rights as interpretive tools and effectively legislated in a vacuum, declaring that equality, dignity and the right to life under Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Constitution demanded immediate protection. Those guidelines remained law until Parliament enacted formal legislation years later. The message was clear: constitutional guarantees could not wait for political convenience.

Two decades later, in 2017, the Court again confronted the intersection of gender and religion in Shayara Bano v Union of India. The practice of instant triple talaq—talaq-e-biddat—allowed a Muslim husband to divorce his wife unilaterally and immediately. In a deeply divided but historic judgment, a majority invalidated the practice, holding that it violated constitutional principles of equality and was manifestly arbitrary. For many women’s rights advocates, it signaled that religious custom could not override fundamental rights.

The following year was transformative. In 2018, the Court delivered Navtej Singh Johar v Union of India, reading down Section 377 of the colonial-era penal code and decriminalising consensual same-sex intimacy between adults. The judgment was not merely technical; it was lyrical, expansive and philosophical. The judges spoke of dignity, privacy, autonomy and the need to protect even a “minuscule minority” from majoritarian prejudice. The decision drew heavily on a 2017 nine-judge bench ruling, Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v Union of India, which had recognised privacy as a fundamental right intrinsic to life and liberty. Privacy, the Court reasoned, includes intimate choice. In linking sexuality to dignity and autonomy, the Court reimagined constitutional equality in deeply personal terms.

That same year, in Joseph Shine v Union of India, the Court struck down the criminal offence of adultery. The law had treated wives as the property of husbands, allowing only men to prosecute and denying women agency. The justices dismantled its patriarchal assumptions, declaring that the Constitution does not permit treating women as subordinate dependents. The adultery ruling, alongside Navtej, reinforced the Court’s willingness to revisit Victorian morality embedded in criminal law.

The Court’s engagement with gender justice has not been confined to sexuality. In 2018, it ruled that the exclusion of women of menstruating age from the Sabarimala temple in Kerala violated constitutional guarantees of equality and non-discrimination. Although implementation has been contentious and review proceedings continue, the decision articulated a powerful doctrine: constitutional morality must prevail over discriminatory custom. The idea that the Constitution embodies transformative aspirations—rather than simply reflecting social tradition—has become a recurring theme.

Transgender rights received a foundational boost in 2014 in NALSA v Union of India, where the Court recognised the right of individuals to self-identify their gender as male, female or third gender. It directed governments to extend affirmative action and protect transgender persons from discrimination. Years before many countries grappled seriously with gender identity law, India’s Supreme Court placed self-identification at the heart of constitutional dignity.

On questions of sexual violence, the Court has oscillated between corrective activism and doctrinal clarification. In 2017, in Independent Thought v Union of India, it read down an exception in rape law that had allowed sexual intercourse with a wife under 18 to escape prosecution. The judgment effectively criminalised sex with a minor wife, addressing the intersection of child marriage and bodily autonomy. In other cases, the Court has intervened to overturn lower court reasoning that appeared to trivialise sexual assault, reinforcing the seriousness of attempted rape and emphasising survivor dignity and anonymity.

Reproductive autonomy has also entered the constitutional fold. In 2022, the Court interpreted India’s abortion framework to allow unmarried women access to termination within specified gestational limits, rejecting distinctions based on marital status. The reasoning again leaned on equality and decisional autonomy, affirming that reproductive choice is not contingent on social approval.

Yet the narrative of relentless progress is incomplete. In 2023, in Supriyo v Union of India, the Court declined to legalise same-sex marriage, emphasising that such reform lay primarily within Parliament’s domain. While acknowledging the dignity of queer relationships and urging the government to address discrimination, the majority stopped short of creating a new marital framework. For critics, the decision revealed institutional limits; for defenders, it reflected respect for separation of powers.

Why, then, does India’s Supreme Court so often appear progressive on matters of gender and sexuality? Part of the answer lies in the Constitution itself. Article 21’s guarantee of life and personal liberty has been interpreted expansively to include dignity, privacy and bodily integrity. Articles 14 and 15 enshrine equality and prohibit discrimination. Together, they provide fertile ground for rights-based expansion. The Court has repeatedly framed itself as the guardian of transformative constitutionalism—a project that seeks not merely to preserve order but to dismantle entrenched hierarchies.

Another factor is procedural. India’s unique Public Interest Litigation system lowers barriers to access, allowing activists and civil society groups to bring structural rights claims. Many landmark cases were the product of years of strategic litigation by women’s organisations, LGBTQ collectives and child rights advocates. When legislatures stall or avoid polarising reforms, the Court often becomes the arena where unresolved social conflicts are constitutionalised.

Institutional self-conception also matters. The Supreme Court occupies a powerful counter-majoritarian position. In times of political flux or social unrest, assertive rights jurisprudence can reinforce judicial legitimacy and public trust. By invoking international conventions and comparative law, the Court situates its reasoning within a global human rights framework, bolstering moral authority.

Still, its activism is selective. The marital rape exception for adult wives remains unresolved, pending further constitutional scrutiny. Implementation gaps persist. Social acceptance lags behind judicial pronouncement. Courtroom victories do not automatically dismantle stigma or violence.

Even so, the Supreme Court of India has undeniably redrawn the legal boundaries of gender, sexuality and sexual autonomy. In a society negotiating tradition and modernity, faith and feminism, family and freedom, the Court has repeatedly declared that the Constitution is not a passive mirror of society but an instrument of transformation. Whether it continues along that path—or retreats into restraint—will shape not only legal doctrine but the lived realities of millions of Indians navigating love, identity and equality in the twenty-first century.

Let me tell you something uncomfortable: when judges start sounding more progressive than politicians, you know society is having an identity crisis.

For years now, India’s Supreme Court has been dragged—sometimes reluctantly, sometimes heroically—into the battlefield of gender, sexuality and sex crimes. And while aunties at family dinners still whisper about “culture” and “tradition,” the bench has been whispering back something far more dangerous: dignity.

When the Court decriminalised same-sex love, it wasn’t just striking down a dusty colonial relic. It was saying that intimacy is not a crime scene. When it recognised transgender persons as having the right to self-identify, it told an entire bureaucracy addicted to forms and boxes that human beings do not fit neatly into either. When it invalidated instant triple talaq, it quietly informed patriarchy that divine convenience does not trump constitutional equality.

Now, before we start lighting incense in honour of judicial sainthood, let’s stay sharp. Courts are not feminist NGOs in robes. They are institutions of power. They move when pushed. Every “historic” verdict was born from years of activists filing petitions, survivors refusing silence, lawyers working pro bono, and communities demanding visibility. The courtroom may deliver the final word, but the script is written in the streets.

Still, we must admit: there is something deliciously subversive about the language the judges have used. Privacy. Autonomy. Constitutional morality. Dignity. These are not small words. They are ideological grenades tossed into drawing rooms where uncles still debate “family honour.” When the Court says that even a “minuscule minority” deserves protection, it is rejecting the tyranny of numbers. That matters.

And yet, progress comes with footnotes. Same-sex marriage? Deferred. Marital rape? Still tangled in legal hesitation. Implementation? Patchy at best. A judgment may sparkle on paper while a queer couple still fears holding hands in public. Law can open doors; it cannot guarantee what waits outside.

So is the Court progressive? Sometimes. Strategic? Certainly. Transformative? Potentially.

Here is the real story: constitutions are not self-executing love letters. They are battlegrounds. When judges choose dignity over dogma, they tilt history—just a little. But the rest of the work belongs to society.

And trust me, aunties like me are watching.