Every Lunar New Year, the world’s largest human migration — China’s Spring Festival travel rush — sends hundreds of millions of people streaming out of megacities and back to ancestral hometowns. But this year, a striking countercurrent has been gathering speed. Known as “reverse travel” or fanxiang chunyun (reverse Spring Festival migration), the trend sees parents boarding trains and planes to visit their urbanised children instead of waiting at home for them to return. During Chinese New Year 2026, this quiet reversal has become one of the most talked-about shifts in holiday mobility, reflecting deeper changes in family life, urban identity and the meaning of reunion itself.

For decades, chunyun (Spring Festival travel rush) has symbolised filial piety in motion. Migrant workers, white-collar professionals and university students would endure overcrowded trains and eye-watering airfares to make it home in time for nianyefan (New Year’s Eve reunion dinner). The emotional weight of “going home” was immense; to miss it risked accusations of forgetting one’s roots.

Official transport estimates again put total journeys this season in the billions, underlining how powerful the tradition remains. Yet data from major travel platforms and state media reporting indicate a surge in tickets booked in the opposite direction. Instead of Shenzhen emptying and small inland towns filling up, retirees from provinces like Henan, Hunan and Sichuan have been travelling toward first-tier cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen. Analysts note particularly sharp increases in bookings by older passengers heading into these urban hubs compared with previous years. The phenomenon has been dubbed fanxiang tuanyuan (reverse reunion), a phrase that captures both logistical inversion and emotional continuity.

The drivers are practical, generational and symbolic all at once. First is sheer convenience. The outbound crush from big cities remains the most intense phase of chunyun. Securing train tickets can feel like winning a lottery; highways clog; flights spike in price. By contrast, seats heading toward the cities are often easier to obtain. Parents, many of them retired and with flexible schedules, can travel earlier or later in the holiday window, smoothing the logistics.

Second is the reality of urban settlement. China’s urbanisation rate has climbed steadily for decades, and many young professionals now own or rent long-term homes in the cities where they work. For them, the metropolis is no longer a temporary stop but a primary residence. Inviting parents to see that life — the apartment they saved for, the office district where they built a career, the skyline that frames their daily commute — carries emotional meaning. It is a subtle declaration: this is my jia (home) now.

State media commentaries have framed reverse travel as an example of evolving family values rather than their erosion. The essence of tuanyuan (reunion) lies not in geography but in togetherness, commentators argue. If the goal of the Spring Festival is to be under one roof, why should that roof be fixed in the ancestral village? In a society where mobility defines opportunity, flexibility around tradition may be a pragmatic adaptation.

The extended public holiday this year has also played a role. With more days off, families can afford longer stays and more relaxed itineraries. Parents who travel to Beijing might tour hutong (traditional alleyways), visit Olympic venues or wander temple fairs. In Shanghai, they stroll along the Bund; in Guangzhou, they sample Cantonese New Year delicacies. What was once a rushed three-day visit home becomes a multi-day urban exploration shared across generations.

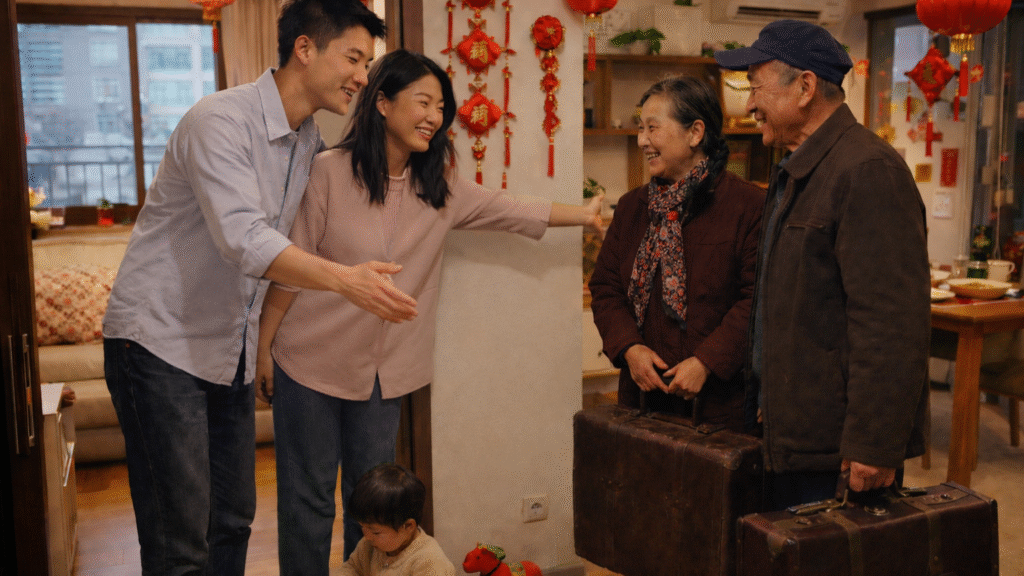

There is also a quiet rebalancing of filial duty. Traditionally, the younger generation demonstrated respect by returning to kneel before elders, offer hongbao (red envelopes) and participate in rituals in the ancestral home. Reverse travel shifts some of the physical burden to parents, but many families interpret it as a joint effort. Younger adults still host lavish nianyefan meals, prepare gifts and organise outings. In interviews with domestic outlets, several urban professionals described pride in showing their parents the fruits of years of hard work.

Economically, the pattern benefits cities that might otherwise empty out during the holiday. Restaurants, tourist attractions and retail districts in major urban centres report steadier foot traffic. Conversely, some smaller towns experience slightly thinner inflows than in peak pre-pandemic years. Transport authorities have welcomed the more diversified flows, noting that reverse travel can ease pressure on heavily saturated outbound routes.

Of course, reverse travel does not replace the traditional homecoming. The vast majority of journeys still follow the classic pattern. For many rural families, ancestral graves must be swept, village rituals observed, and extended kin visited in person. In some regions, the social expectation of returning remains strong. A son or daughter who fails to appear at the family table may still be the subject of pointed questions.

But the symbolic shift matters. Sociologists point out that the meaning of “home” in contemporary China is increasingly plural. Young urbanites often maintain emotional ties to their birthplace while investing financially and socially in their city life. Reverse travel embodies that duality. Parents stepping off high-speed trains into glittering station halls are not abandoning tradition; they are entering their children’s new world.

There is also an intergenerational curiosity at play. For parents who spent most of their lives in smaller communities, visiting megacities offers a glimpse into the scale of change that has transformed China in a single generation. Skyscrapers, metro systems, digital payment kiosks and cosmopolitan neighbourhoods can be both overwhelming and awe-inspiring. Sharing that experience over hotpot or dumplings creates a new kind of family memory.

Critics worry that the shift could accelerate the hollowing out of rural life, reinforcing urban centrality. Yet others argue it reflects a mature, flexible society where tradition adapts to economic geography. After all, the core of the Spring Festival has always been renewal and reunion, not strict adherence to a single itinerary.

As lanterns glow and firecrackers echo, the image of migration itself is being quietly rewritten. The great outward tide from cities now meets an inward flow of parents carrying homemade sausages, pickles and the stubborn love of a generation that once stayed put. In that crossing of directions — trains passing in opposite lanes, airport halls filled with both departures and arrivals — lies a portrait of modern China: mobile, pragmatic, still anchored in family, but willing to redefine where “home” truly is.

Ah, reverse travel. Finally, a Lunar New Year plot twist I can get behind.

For decades, the emotional blackmail of chunyun went like this: if you truly loved your parents, you would crawl across three provinces on a sold-out train, wedged between instant noodle fumes and someone’s restless toddler, just to appear at the ancestral dining table in time for nianyefan. Romance? Optional. Career? Negotiable. But reunion dinner? Non-negotiable.

And now? The children say, “Mama, Baba — you come here.”

I love it. Not because tradition should be thrown into the Yangtze, but because this is what living traditions do: they stretch. They adapt. They breathe.

Let’s be honest. Many of these young urban professionals have built lives in cities that are not temporary stepping stones but permanent homes. They’ve sweated through 996 work culture, saved for microscopic apartments with heroic mortgages, and navigated metros like battlefield generals. Why shouldn’t their parents see that? Why shouldn’t “home” include the place where their children have fought to stand upright in modern China?

Reverse reunion travel — fanxiang tuanyuan — is not rebellion. It’s negotiation.

It says: we still value tuanyuan (togetherness), but we refuse to equate filial piety with physical exhaustion. It says: family is about presence, not postal codes.

And there’s something quietly radical about parents boarding high-speed trains to their children’s cities. It shifts the power dynamic, just a little. For one holiday, the adult child becomes host. The parent steps into the child’s world — sees the office tower, the trendy hotpot place, the tiny balcony garden. It humanises the younger generation’s choices. It says: I recognise your life as real.

Does this weaken rural roots? Perhaps in some cases. But nostalgia has never been a development strategy. China’s story is urbanisation, mobility, reinvention. Expecting emotional geography to stay frozen while economic geography transforms is unrealistic.

What moves me most is the image of crossing trains — some racing outward, some inward — carrying homemade sausages in one direction and city gift boxes in the other. Two Chinas meeting in motion.

Spicy Auntie’s verdict? Let the direction flip. Let parents see the skyline. Let children cook in their own kitchens. Tradition that cannot travel both ways becomes a cage. Tradition that can reverse course becomes a bridge.

And bridges, my darlings, are far more useful than cages.