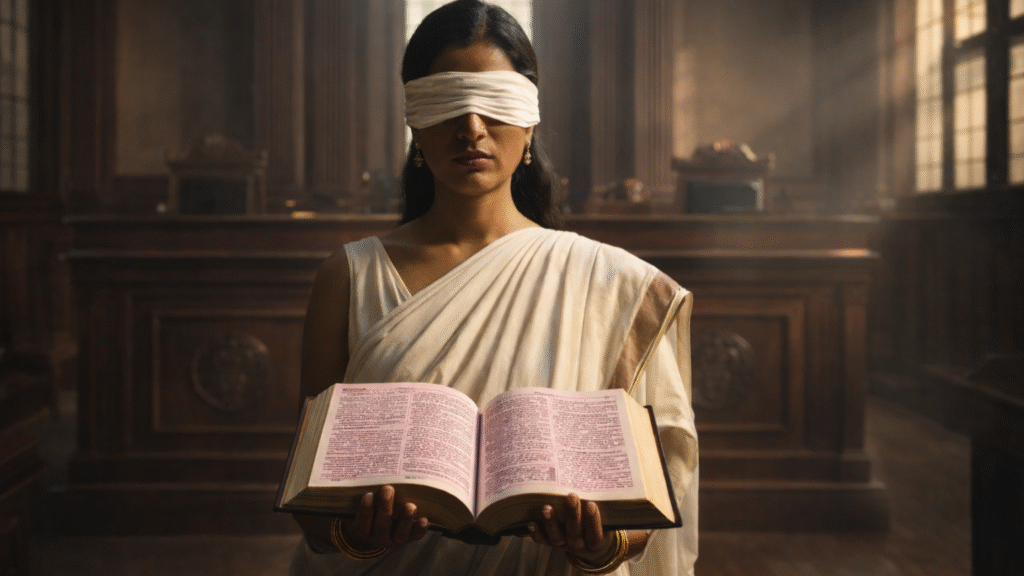

On an August morning in 2023, India’s Supreme Court tried something quietly radical: it published a style guide. Not for commas or Latin maxims, but for the everyday vocabulary and “common sense” assumptions that slip into courtrooms—and then harden into law’s version of reality. The document was titled the Handbook on Combating Gender Stereotypes, released under then Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud. He framed it not as a moral scolding of earlier judges, but as a practical warning: words that feel routine in legal writing can carry a lifetime of bias, and courts often “perpetuate [stereotypes] inadvertently.”

In the foreword, Chandrachud expresses the hope that it will be widely read so that legal reasoning and writing can be “free of harmful notions about women,” calling it part of a longer quest for a “gender-just legal order.” In other words, the Court wasn’t pretending a glossary can fix misogyny; it was claiming, more modestly, that language is one place the judiciary can start cleaning its own house.

The handbook’s purpose is straightforward: help judges and lawyers “identify, understand and combat” stereotypical language, especially in pleadings, orders and judgments. It does this through three main moves. First, it names the problem: stereotypes aren’t only insults; they are shortcuts—assumptions about what “good” women do, what “real” victims look like, who is credible, who is “respectable,” who is “promiscuous,” who is “family-oriented,” who is “asking for it.” Second, it supplies replacement language: the handbook’s best-known section is its glossary of “gender-unjust” terms and preferred alternatives. Third, it goes beyond vocabulary and tackles reasoning: it catalogues the kinds of courtroom logic that smuggle stereotypes into findings about consent, credibility, character and “normal” behaviour.

The glossary is where the handbook became instantly quotable—and, inevitably, meme-able. It tells courts to ditch phrases that come loaded with judgement, like “eve teasing” (as if harassment is flirtation), and to use plain descriptions like “street sexual harassment.” It recommends “menstrual products” rather than “feminine hygiene products,” and warns against “provocative dress” as a courtroom label, suggesting simply “clothing/dress.” Some replacements are deliberately literal, almost clinical, because the point is to remove moral smoke from the evidence: “adulteress” becomes “woman who has engaged in sexual relations outside of marriage,” and “good wife/obedient wife” becomes simply “wife.” The most debated example—because it sounds awkward on the tongue—is the handbook’s suggestion to avoid “concubine/keep” and instead write “woman with whom a man has had romantic or sexual relations outside of marriage.” The handbook is not trying to write poetry. It is trying to force legal prose to describe relationships without importing contempt.

In late 2023, the handbook itself became a site of controversy when the Supreme Court updated terms relating to commercial sexual exploitation. Bar & Bench reported that, on advice from anti-trafficking NGOs, the Court would replace “sex worker” with phrases such as “trafficked survivor,” “woman engaged in commercial sexual activity,” and “woman forced into commercial sexual exploitation.” This revealed a tension baked into language reform: replacing a stigmatizing word can either de-stigmatize—or erase agency—depending on what reality the replacement assumes.

Beyond the glossary, the handbook’s most serious pages are about how stereotypes warp adjudication, particularly in sexual-violence cases. It pushes back against the familiar courtroom myths: that a survivor’s clothing, drinking, or social life implies consent; that “real” victims behave in one predictable way; that delayed reporting automatically means fabrication; that assault is most likely committed by strangers rather than people known to the survivor; and that caste, disability, or age can be used as lazy proxies for “probability.” The point is not to teach judges empathy in the abstract, but to stop them from turning social prejudice into “reasonable inference.”

So what use has actually been made of it? The honest answer is: uneven, and sometimes reluctant. There are instances where courts have invoked the handbook as a benchmark for acceptable language. Bar & Bench reported a Delhi High Court observation in September 2023 that derogatory language in pleadings fell below the standards laid down in the Supreme Court’s handbook, while the court was cautioning trial courts against remarks in bail orders that could look like final conclusions. But there are also examples that read like judicial pushback. In March 2025, a Madras High Court judgment, while discussing whether a term like “concubine” should be avoided, noted the Supreme Court’s handbook and then remarked—politely but pointedly—that the suggested alternative reads more like a “description” than a definitional term. In other words, the handbook’s influence can appear as a nudge, not a rule: some judges adopt it, some quote it, some argue with it.

By February 2026, the debate moved from whether the handbook was needed to whether it was usable. News reports said the current Chief Justice of India, Surya Kant, criticised the 2023 handbook as overly technical—“too ‘Harvard-oriented’”—and questioned its practical value for survivors and ordinary citizens, while the Court directed the National Judicial Academy (Bhopal) to work on new guidelines and report back. That criticism matters because it exposes a final truth about the handbook: it lives or dies not as a PDF, but as training, habit, and institutional culture. A glossary can change how a judgment reads. Only a judiciary that wants to change can alter what a judgment does.

Hundreds of pages of patriarchy have been written in India’s courtrooms over decades — sometimes in the name of “tradition,” sometimes in the name of “morality,” and often in the name of “common sense.” So when the Supreme Court decided in 2023 to publish a Handbook on Combating Gender Stereotypes, some people rolled their eyes. A style guide? Really? Is sexism going to disappear because judges swap a few words?

Well. Let me tell you something, my darlings: words are never “just words.”

When a court calls sexual harassment “eve teasing,” it shrinks violence into flirtation. When a judgment describes a woman as a “good wife” or hints that her clothes were “provocative,” it is not neutrally describing facts — it is quietly telling society what a “good woman” should look like. And when that language is stamped with the authority of the highest court in the land, it travels far beyond the courtroom. It becomes culture.

So yes, a handbook matters.

It matters because it forces judges — those solemn men and women in black robes — to confront the lazy assumptions that sometimes slip into their reasoning. It matters because survivors of assault deserve to be described without moral commentary attached to their hemlines. It matters because the judiciary, of all institutions, should understand the power of narrative.

Now, is the handbook perfect? Of course not. Some of its suggested replacements sound like they were drafted by overcaffeinated law professors. And the recent debate about whether it is too “Harvard-oriented” makes me smile a little. Patriarchy has survived millennia — it can survive a few awkward phrases.

But here’s the real question: will judges actually use it?

A PDF cannot dismantle bias. A glossary cannot cure misogyny. What changes justice is habit — what judges choose to notice, what they refuse to assume, what they strike out before signing their names.

Still, symbolism matters. When the Supreme Court says, “We will not use language that demeans women,” it sends a signal to every lower court, every lawyer, every police officer drafting a chargesheet.

And perhaps, slowly, to every father teaching his son what women are “supposed” to be.

So no, Auntie doesn’t think this handbook will topple patriarchy tomorrow. But if it makes even one judge pause before writing “she behaved like a modern woman,” then darling, that pause is progress.