In Japan’s February 2026 snap election, headlines focused on political stability and a decisive mandate — but beneath the surface, a troubling statistic emerged: fewer women were elected to the House of Representatives, despite a record number running and the country being led by its first female prime minister. The decline in female lawmakers has reignited debate about gender equality in Japanese politics, exposing the gap between symbolic breakthroughs and structural reality. As Japan navigates economic uncertainty, demographic decline and regional security tensions, the question is no longer whether women can lead — it is why so few are allowed to share power in the first place.

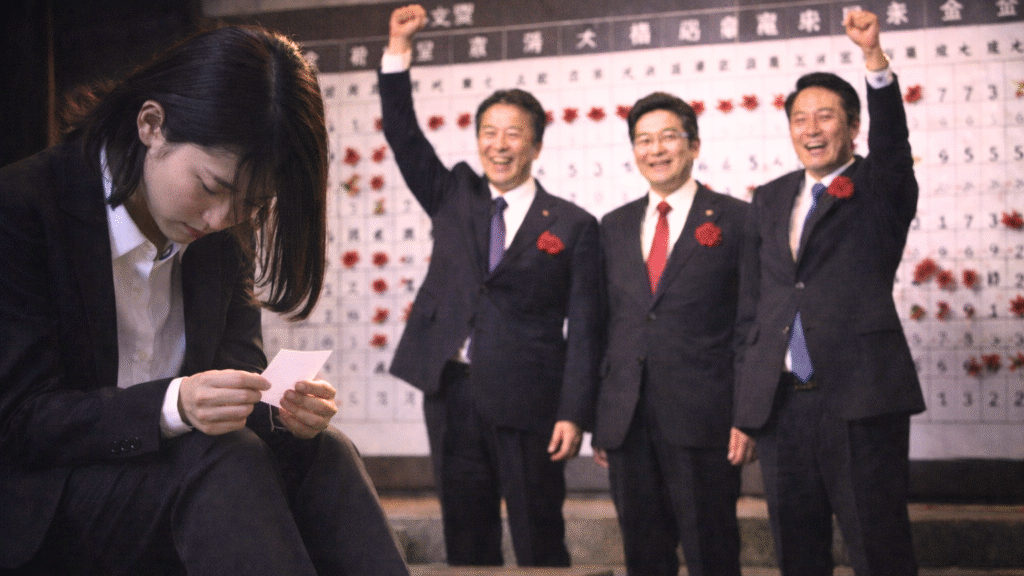

Sanae Takaichi’s LDP-led coalition captured 316 out of 465 seats, one of the strongest mandates in recent decades. Her own ascent remains historic: she is the first woman to hold the office of shushō (首相, prime minister) in Japan’s modern political history. Yet her breakthrough has not translated into broader female representation. While a record 24 percent of candidates in this election were women, only 68 won seats — down from 73 in the previous lower house. Women now hold roughly 15 percent of seats, leaving Japan near the bottom among advanced democracies for parliamentary gender balance.

The paradox is striking. Symbolically, Japan appears to be turning a page. Substantively, little has changed. The World Economic Forum’s latest Global Gender Gap rankings continue to place Japan well below most OECD countries in political empowerment, despite improvements in education and workforce participation. Politics remains the stubborn frontier.

Within the LDP itself, the pipeline problem is glaring. The party fielded relatively few female candidates in winnable districts, and most senior leadership positions remain male-dominated. Takaichi did endorse several women, including Hikaru Fujita, who drew national attention for campaigning while pregnant and speaking openly about childcare policy and support for working mothers. But such examples remain exceptions rather than the rule.

Cultural undercurrents run deep. The long-standing ideal of ryōsai kenbo (良妻賢母, “good wife, wise mother”) continues to shape expectations about women’s primary role in society. Although Japanese women are among the most highly educated in Asia, and workforce participation has increased steadily, political ambition often collides with expectations around caregiving and domestic responsibilities. Running for office in Japan demands intense retail campaigning, fundraising networks, and party backing — systems historically built and dominated by men.

There are institutional hurdles as well. Japan’s 2018 gender parity law encourages political parties to field equal numbers of male and female candidates, but it carries no penalties for non-compliance. As a result, progress depends largely on party will rather than legal obligation. Opposition parties have generally nominated more women proportionally, yet their weaker electoral performance limits overall gains in representation. At the same time, the electorate itself appears less resistant to female candidates than party structures might suggest. Surveys consistently show that voters do not strongly discriminate against women at the ballot box. In urban districts especially, younger voters express support for more inclusive leadership. The bottleneck lies earlier — in recruitment, mentorship, funding and internal party promotion.

There are also generational shifts underway. Younger female politicians are leveraging social media, building grassroots networks, and reframing political narratives around work-life balance, demographic crisis and social care. Japan’s rapidly aging society and falling birthrate have placed family policy at the center of national debate. Ironically, these are areas where female lawmakers often bring lived experience and policy focus — yet they remain underrepresented in shaping the solutions.

Takaichi herself embodies another layer of complexity. While her election shattered a glass ceiling, her conservative positions on issues such as separate surnames for married couples and constitutional revision align closely with the LDP’s traditional base. For critics, her leadership demonstrates that a woman at the top does not automatically equate to feminist reform. For supporters, her rise proves that gender need not define political capability. Both arguments coexist in Japan’s current discourse.

International comparisons sharpen the contrast. Several Asian neighbors — including South Korea and Taiwan — have seen stronger momentum in female political leadership over the past decade. In Europe, quota systems have significantly increased women’s parliamentary presence. Japan’s incremental approach, reliant on voluntary party commitments, has produced slower and sometimes reversible gains.

As the new Diet convenes in Nagatachō, Japan’s political heart, the numbers tell a sobering story. A record number of women stepped forward to run, yet fewer now sit in the kokkai (国会, National Diet). The gap between aspiration and outcome underscores how entrenched structures resist even symbolic breakthroughs. The February snap election may be remembered for delivering political stability. But it should also be remembered as a moment of reckoning. If Japan is serious about revitalizing its democracy and addressing the social challenges ahead — from economic reform to caregiving infrastructure — it cannot afford to sideline half its population from meaningful representation. A female prime minister is a milestone. A legislature that reflects the diversity of the society it governs would be transformation.

So let me get this straight, darlings. Japan finally elects its first woman prime minister, and the reward for that historic breakthrough is… fewer women in parliament? If irony were a political system, we would call it proportional representation.

I have spent enough time in Nagatachō corridors and East Asian power circles to know that symbolism and substance are very different creatures. A woman at the top does not automatically open the floodgates for other women. Sometimes she simply proves that one exceptional woman can survive in a system still designed by and for men. That’s not revolution. That’s adaptation.

Japan’s political culture remains wrapped in the old ryōsai kenbo fantasy — the “good wife, wise mother” who supports the state quietly from the kitchen while the men make speeches about the nation. The modern version is more polished: highly educated women, impeccably dressed, managing both careers and households without complaint. But when it comes to party nominations, campaign funding, and backroom negotiations, the old boys’ networks still hum like a well-oiled karaoke machine at midnight.

And here’s what really fascinates me: voters themselves are not the main obstacle. Poll after poll shows that Japanese citizens are perfectly willing to vote for women. The bottleneck happens before the ballot — inside party headquarters, inside funding committees, inside expectations about who “looks” like a serious candidate. Politics is still treated as a full-contact sport requiring total availability, which conveniently assumes someone else is cooking dinner and raising the children.

Meanwhile, Japan is facing a demographic cliff. Low birthrates, aging society, caregiving crises — these are not abstract policy debates. They are lived realities. Who understands them more intimately than women juggling work, parents, and school schedules? And yet the chamber making decisions about childcare budgets and workplace reform remains overwhelmingly male.

Now, I am not naïve. A female prime minister is no small thing. It matters. Representation matters. But representation at the summit without depth beneath it is fragile. Real change is not about one woman breaking through the ceiling; it is about rebuilding the house.

So my gentle provocation to Japan is this: don’t be satisfied with the photo opportunity. Don’t confuse a headline with a transformation. If democracy is meant to reflect society, then society’s women deserve more than symbolic applause. They deserve seats, power, and the unapologetic right to shape the future.