In a landmark legal case that has reverberated across Malaysia and sent shockwaves through its LGBTQ+ communities, a trans woman in the northeastern state of Kelantan has become the first person in Malaysian history to be formally charged in a Syariah (Islamic law) Court solely for changing her gender — a move that civil liberties activists say underscores deepening tensions between personal freedoms and religious legal frameworks in the country. This unprecedented case, heard in the Kota Bharu Syariah Court earlier this year, is the first prosecution under Section 18 of the Syariah Criminal Code (I) 2019, a provision that criminalises gender transition, punishable by up to RM3,000 in fines, a two-year jail term, or both.

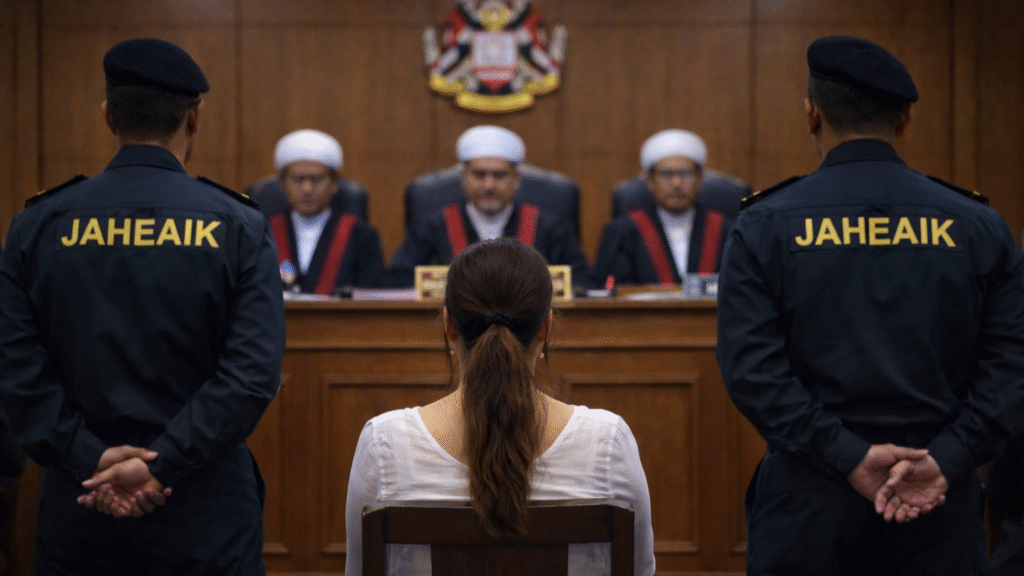

The accused, whose identity has been legally protected and not disclosed publicly, was arrested in an operation by the Kelantan Islamic Affairs Department (known locally as Jabatan Hal Ehwal Agama Islam Kelantan, or JAHEAIK) during an event involving members of the transgender community. According to sources cited by media, she pleaded not guilty when the charge was initially brought, and the case remains in the “management stage” as the court prepares for further proceedings.

Kelantan’s strict enforcement of Syariah law — where the state government holds significant autonomy over matters of Islamic jurisprudence — has increasingly put transgender and gender-diverse people in the spotlight. While Malaysia’s dual-track legal system allows both civil and Syariah courts to operate, the Federal Constitution limits the scope of state religious laws where they conflict with national law. In Nik Elin v. Kelantan, the Federal Court in 2024 struck down several Kelantan Syariah enactments for exceeding constitutional boundaries, but the legislation criminalising gender change remains on the books.

For many Malaysians, especially those who identify as transgender or gender non-conforming, this prosecution lays bare the everyday reality of navigating personal identity within a legal landscape that often conflates gender with religious doctrine. Transgender individuals in Malaysia have long faced legal and social barriers. In some states, laws dating back decades criminalised individuals for “cross-dressing” — broadly interpreted as a person wearing attire associated with the opposite sex — and saw periodic enforcement actions. Notably, a 2015 case in Kelantan resulted in nine transgender women being convicted under such provisions, a decision that drew criticism from human rights defenders who argued that these laws infringed on fundamental rights like freedom of expression.

Advocates such as Thilaga Sulathireh, co-founder of Justice for Sisters, have warned that provisions like those in Kelantan’s Syariah Criminal Code criminalise deeply personal decisions about one’s own body and identity, contributing to fear, stigma, and a chilling effect on the community’s willingness to seek health care or social support. In media reports, Sulathireh has noted that Kelantan is currently the only Malaysian state with a specific legal clause that explicitly criminalises gender reassignment.

The echo of this case also brings to mind earlier high-profile incidents involving transgender Malaysians. One prominent example is Nur Sajat, a transgender entrepreneur and social media influencer who faced multiple Sharia-related charges in Malaysia and ultimately sought asylum in Australia in 2021 due to safety concerns and the threat of legal action. Her situation highlighted longstanding debates around gender recognition, citizenship documentation, and personal safety that many transgender people in Malaysia confront.

Culturally, transgender people in Malaysia occupy a complex position. In Malay language and culture, terms like “mak nyah” have been adopted by the community itself — a term that carries a sense of identity and solidarity within various social circles. Yet at the same time, state-enforced interpretations of Syariah can impose criminal sanctions that contradict lived realities. Human rights organisations have repeatedly underscored that laws targeting transgender individuals not only chill personal freedoms but also risk contributing to discrimination, harassment, and violations of privacy and dignity.

Supporters of the Kelantan government’s stance argue that moral and religious codes underpinning Syariah are essential to upholding societal values within the state, which is known for its conservative policies and adherence to Islamic principles. However, critics see this first gender transition prosecution as part of a worrying trend that could encourage further legal action against transgender communities, especially in a region where public discourse on gender diversity remains fraught and heavily politicised.

As this case unfolds, it is likely to attract heightened national and international attention — not just as a legal milestone, but as a lived story about identity, rights, and the push-and-pull between personal autonomy and religious law in 21st-century Malaysia. The outcome could have implications not only for transgender people in Kelantan but for wider debates on gender, law and human rights across Southeast Asia.

I’ve said enough about Kelantan. About its undang-undang zalim (cruel laws). About politicians who wrap intolerance in piety and call it governance. About moral policing that somehow never seems to catch corruption, domestic violence, or child marriage, but has laser focus on what adults do with their own bodies. Enough. I’m bored of lecturing power.

Now it’s time to talk about the people being crushed under it.

Because behind every “historic case” and every dry legal phrase like pertukaran jantina (gender change) is a human being who woke up that morning needing to breathe, work, eat, love, and survive — just like everyone else. A person who already knows what it costs to be visible. A person who has already paid in fear, family rejection, lost jobs, whispered insults, and the constant calculation of safety. And then the state shows up and says: we will add court dates to your trauma.

Kelantan’s favourite fiction is that transgender people are a Western import. Rubbish. Mak nyah have existed in Malay society longer than most of today’s politicians have been alive. They were hairdressers, performers, caretakers, neighbours. Not perfect angels — just people. What changed wasn’t their existence; what changed was the appetite for punishment.

Let’s be honest about who pays the price of these laws. Not ministers. Not religious officials with government salaries. Not the men who draft legislation and then go home untouched. The cost is paid by people already living at the margins — those with fewer family buffers, fewer savings, fewer exits. When you criminalise identity, you don’t erase it. You drive it underground, where violence, exploitation, and despair thrive.

And don’t insult us by pretending this is about “guidance” or nasihat (moral advice). Guidance doesn’t come with handcuffs. Faith doesn’t need court summons. If your belief system collapses because someone else lives differently, the problem isn’t them — it’s the fragility of your certainty.

What I want, just once, is for the conversation to centre the victims instead of the lawmakers. Ask what it feels like to be reduced to a legal experiment. Ask what it means to plan your life around raids and arrests. Ask why survival itself is treated as defiance.

Kelantan will keep passing laws. Politicians will keep posturing. But history has a habit of remembering the harmed more clearly than the loud. And one day, when these cases are footnotes in dusty law journals, the real question will be simple: who stood with the people being punished for existing — and who chose comfort over courage?

Spicy Auntie already knows her answer.