The image of a woman at the pinnacle of Japanese politics was always going to collide with the most immovable symbols of tradition, and few are heavier with history than sumo. When Japan’s first female prime minister, Sanae Takaichi made it clear that she would not step onto the sumo ring and would not challenge the long-standing rule excluding women from the dohyō (sumo ring), the decision immediately rippled far beyond the sport itself. It touched nerves around gender equality, religious custom, political caution and the limits of change in contemporary Japan—keywords that have driven the debate across domestic and international media in recent weeks.

The prime minister’s position has been consistent and carefully worded. She has said she respects dentō (tradition) and bunka (culture), and that professional sumo’s customs should be left to the Japan Sumo Association rather than reshaped by political intervention. In practice, this means continuing the ritual whereby the prime minister’s trophy is presented by a male representative inside the ring, while the elected leader remains ringside. For supporters, this is an example of restraint and respect for cultural autonomy. For critics, it is a missed opportunity—especially symbolic given the historic significance of a woman occupying the country’s highest office.

To understand why the issue is so charged, it helps to grasp what the dohyō represents. In professional sumo, the ring is treated as a sacred space, purified with salt and rooted in Shinto ritual. The exclusion of women is often explained through the concept of nyonin kinsei (prohibition of women), an idea historically linked to notions of ritual purity rather than modern biology. While this belief has faded in many religious contexts, it remains firmly embedded in professional sumo, even as the sport markets itself globally as a national treasure.

Reactions to the prime minister’s stance have been divided. Conservative commentators and some senior figures within the sumo world praised the decision as sensible and non-confrontational, arguing that political power should not be used to override cultural institutions. Several columnists in mainstream newspapers framed it as an example of wakimae (knowing one’s place), a quality still valued in Japanese leadership. Others, including women’s rights advocates and younger commentators, were far less forgiving. On social media, critics argued that “respecting tradition” too often becomes a convenient phrase to justify gender exclusion, especially when change might provoke backlash.

International reactions have also been pointed. Foreign media outlets revisited earlier controversies, such as incidents in which women were asked to leave the ring even during medical emergencies, highlighting how the rule clashes with global norms around equality. Some observers noted the irony of Japan promoting women’s leadership abroad while hesitating to confront symbolic discrimination at home. The prime minister’s defenders countered that symbolism alone does not equal policy, pointing to her stated support for women’s participation in the workforce and leadership in other sectors.

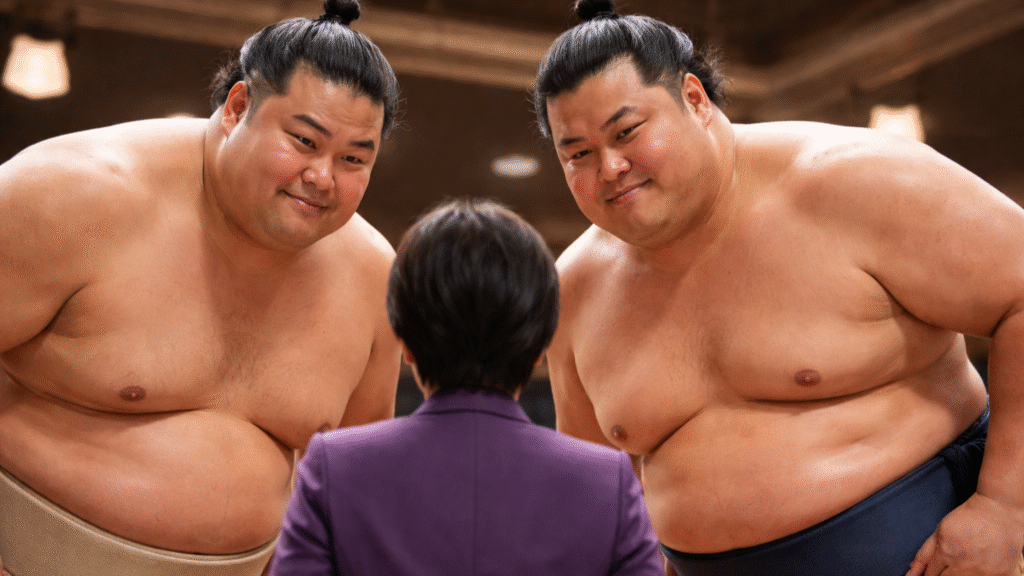

What complicates the picture is that women in Japan have never fully accepted sumo’s exclusion quietly. Outside the professional arena, onna-zumō (women’s sumo) has a long if marginal history, from local festivals to school competitions. In recent years, informal and community-based women’s sumo groups have emerged, some playful, some serious, reclaiming the physicality and joy of the sport without waiting for institutional permission. As we noted in a blog post months ago, these grassroots competitions are less about overthrowing tradition than about creating parallel spaces where women can grapple, laugh, train and compete on their own terms.

Seen in this light, the prime minister’s decision may slow institutional change, but it has not stopped cultural evolution. Many Japanese women interviewed by the press expressed disappointment, but also pragmatism. “Sumo will change last,” one Tokyo-based commentator remarked, “because it carries the weight of myth.” Others suggested that real transformation may come not from the top, but from shifting attitudes among younger generations who are less attached to rigid ideas of purity and gender roles.

For now, the dohyō remains male-only, and the prime minister has chosen caution over confrontation. Whether history judges that as wisdom or timidity will depend on what follows. If respect for tradition coexists with meaningful progress elsewhere, the decision may fade into a footnote. If not, it risks becoming a symbol of how power, even in female hands, can still stop short of challenging the most entrenched lines drawn around women’s bodies and spaces.

I have a complicated relationship with tradition. I respect it when it holds stories, skills, beauty, memory. I have far less patience when it is used as a velvet rope to keep women quietly outside, smiling politely while men perform rituals about strength, purity, and power. So when Japan’s prime minister calmly announced that she would not step onto the dohyō (sumo ring) and would not challenge the rule excluding women, my first reaction was not shock. It was a tired sigh. Ah yes. That tradition.

Let’s be honest: this was never really about sumo. Sumo just happens to be one of the last places in modern Japan where nyonin kinsei (women prohibited) can still be defended with a straight face, wrapped in Shinto language about impurity and sacred space. The ring is holy, we are told. Women’s bodies are… inconvenient. Or disruptive. Or risky. Pick your euphemism. The salt gets thrown, the myths get polished, and the exclusion stays intact.

What disappointed me was not that the prime minister respected tradition. It was that she chose non-interference as her legacy move in a moment thick with symbolism. No one asked her to wrestle. No one asked her to smash the Japan Sumo Association with a feminist hammer. Even acknowledging the discomfort, the contradiction, the tension—saying “this makes me uneasy”—would have mattered. Instead, we got reassurance. Calm. Continuity. The political equivalent of stepping back so the men can get on with it.

I’ve seen this move before, across Asia. Women rise to power and are immediately expected to prove they are not too much. Not too loud. Not too disruptive. Not the kind of woman who makes everyone uncomfortable by asking why certain spaces are forever closed to us. The irony, of course, is that sumo is literally about bodies colliding. But not women’s bodies. Those remain taboo.

And yet—this is where I refuse to end on despair—Japanese women are not waiting for permission. They never have. From informal onna-zumō gatherings to playful, defiant community tournaments, women have already claimed the joy, sweat, and absurdity of the sport in their own spaces. They don’t need a prime minister’s blessing to grapple, laugh, and fall flat on the clay. They are doing it anyway, quietly undermining the myth that sumo without exclusion somehow loses its soul.

So yes, the dohyō stays closed. For now. But culture is not only what institutions defend; it is what people practice. And somewhere far from the televised tournaments, women are wrestling—not just with each other, but with the idea that tradition must always mean obedience. On that ring, at least, I know who I’m cheering for.