Short for sinema elektronik, Sinetron is Indonesia’s long-running television drama industry, born in the early 1990s when private broadcasters replaced a struggling national film sector with fast, inexpensive serial storytelling. Designed for daily viewing and shaped by ratings, advertising, and moral regulation, sinetron quickly became the country’s most powerful popular narrative form. More than just entertainment, it functions as a mass social classroom, repeatedly teaching audiences what love, marriage, ambition, failure, and virtue should look like. At the center of this universe stands one figure above all others: the woman.

The most recognizable woman in Sinetron is the suffering heroine, often young, modest, and poor. She is patient (sabar), emotionally restrained, and endlessly forgiving. Her life is defined by endurance: abusive in-laws, infidelity, class humiliation, and repeated injustice. Yet she rarely rebels. Her virtue lies in acceptance (ikhlas), and the narrative rewards her not with independence but with moral vindication—usually through marriage, reconciliation, or belated recognition of her purity. Agency is replaced by perseverance, and happiness is something granted, not chosen.

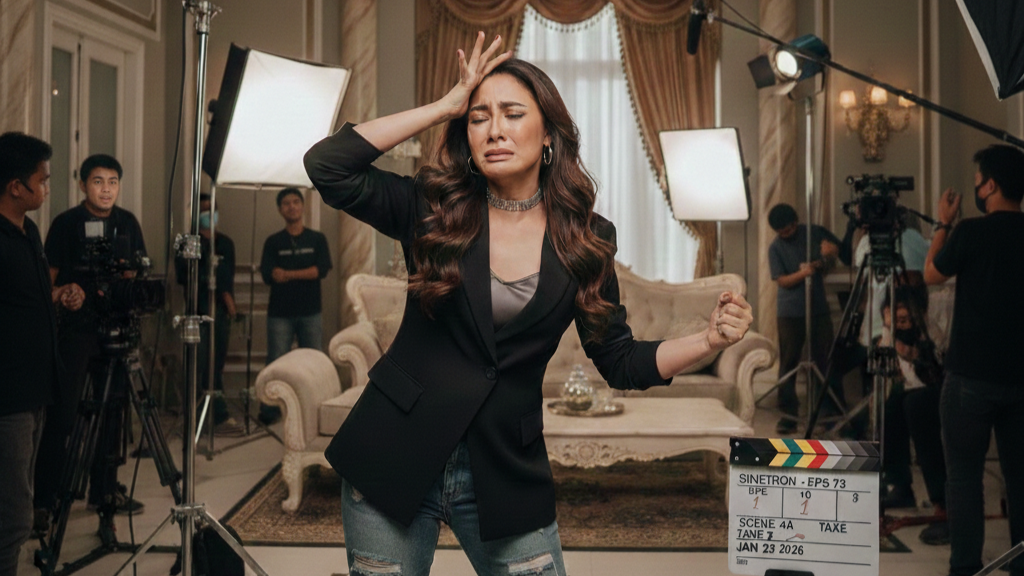

Opposite her stands the glamorous antagonist, a woman who dares to want more. She is rich or upwardly mobile, stylish, outspoken, often sexually confident. In sinetron logic, these traits are inseparable from moral danger. She manipulates, seduces, schemes, and disrupts households. Her independence is portrayed not as strength but as excess, and her desire—whether for love, power, or status—is coded as selfish. The narrative punishes her predictably: abandonment, infertility, madness, or public disgrace. If the good woman suffers quietly, the bad woman acts—and is disciplined for it.

Another central figure is the wife, particularly the legally sanctioned first wife. Marriage in sinetron is not a partnership but a moral hierarchy, and the wife’s value is measured through loyalty, patience, and endurance. Even when betrayed, she is expected to preserve the family unit. Divorce is treated as tragedy or moral failure, not liberation. The wife who stays, forgives, and absorbs pain is framed as noble; the wife who leaves is often portrayed as unstable or selfish. Matrimony remains the ultimate proof of feminine worth.

Closely linked is the figure of the other woman—the mistress or second wife. She exists to threaten domestic order and to dramatize female rivalry. Her story rarely explores structural inequality or male power; instead, conflict is feminized and personalized. Women fight women, while male infidelity is normalized or excused as weakness. Redemption is possible only through repentance, disappearance, or death. Love, for her, is never a legitimate claim.

In religious Sinetron, especially during Ramadan, women appear as moral custodians of faith. These characters embody piety, modest dress, and emotional sacrifice. Female repentance arcs are common: a fallen woman finds redemption through suffering, obedience, and renewed religiosity. Men may sin, but women must restore moral balance. Piety becomes a form of discipline, and femininity is tied directly to spiritual responsibility.

The career woman occupies an uneasy space. She may be competent, educated, and economically useful, but her ambition is always provisional. Professional success must not challenge male authority or replace marriage and motherhood. If she prioritizes work too openly, she risks being reframed as cold, arrogant, or unfulfilled. The narrative often resolves her story by domesticating her ambition—through romance, compromise, or retreat from power.

Single mothers and widows appear frequently, yet rarely as empowered figures. They are portrayed as figures of endurance, deserving sympathy but not aspiration. Their independence is tolerated only because it is forced by tragedy. Desire is muted, romance is risky, and their social position remains precarious. The message is clear: womanhood outside marriage is survivable, but never ideal.

These archetypes are not accidental. They are shaped by advertiser expectations, mass-audience conservatism, and the moral boundaries enforced by Komisi Penyiaran Indonesia (Indonesian Broadcasting Commission), which prioritizes “decency,” “family values,” and social harmony. Together, these forces produce a television landscape where women carry the emotional, moral, and symbolic weight of society.

Despite cosmetic changes—better production values, younger casts, more urban settings—the underlying logic remains strikingly consistent. Sinetron women may cry, endure, repent, and occasionally triumph, but they are rarely allowed to choose freely. In Indonesia’s most popular stories, femininity is still a test of patience, sacrifice, and moral restraint—and the drama lies not in transformation, but in how much a woman can bear before being deemed worthy of happiness.

Auntie has a confession. After watching enough sinetron to qualify for emotional compensation, I’ve realized something important: Indonesian television does not want women to be happy. It wants them to be patient. Preferably while crying, forgiving, and waiting for a man to notice their moral superiority sometime around episode 347.

In sinetron-land, the ideal woman is a saint with tear ducts. She is poor but pure, wronged but grateful, betrayed but still ironing shirts. Her superpower is not intelligence or courage, but sabar. Endless, weaponized patience. If she ever gets angry, it’s temporary and followed by guilt, prayer, or a fainting spell.

Now, let’s talk about the other women. You know the ones. The ones with lipstick budgets, opinions, and jobs. The “rich wife,” the “career woman,” the woman who dares to want something. These women exist for one reason only: to be punished. Their crimes include ambition, sexual confidence, and—this is unforgivable—refusing to suffer quietly. By the final act, they will be infertile, abandoned, humiliated, or repentant in beige clothing.

And marriage? Oh, marriage is not a partnership. It is a moral exam women keep retaking. The wife who stays is noble. The wife who leaves is unstable. The mistress is evil incarnate, while the husband is just “weak.” Men wander; women must absorb the consequences. Female rivalry gets all the screen time, while male accountability quietly exits the studio.

Auntie especially loves religious sinetron season, when women become full-time moral janitors. Men sin; women cleanse. Women repent; women forgive; women restore cosmic balance. Apparently God is very busy and outsourced morality to mothers and wives.

Career women? Allowed—briefly. As long as work doesn’t replace marriage, challenge male authority, or make her look satisfied. If she enjoys her independence too much, don’t worry: romance will domesticate her by episode 60.

All this is presented as “family values,” carefully approved by Komisi Penyiaran Indonesia, advertisers, and the sacred altar of ratings. And so sinetron keeps telling millions of women the same bedtime story: endure now, maybe be rewarded later, don’t choose too freely.

Auntie watches, rolls her eyes, and pours another coffee. Because if Indonesian women really behaved like sinetron heroines, nothing would ever change—and Auntie would be very, very bored.