A dark digital underworld hums quietly but urgently in South Korea. In the past year alone, the National Police Agency (NPA) detected 3,411 cases of online sexual abuse and detained 3,557 people between November 2024 and October 2025. And nearly half of those arrested were teenagers.

Once used to be called “몰카” (molka)—secret-spy-cam footage shot in bathrooms or changing rooms—digital sex crimes in South Korea have now morphed into something more complex and insidious. The latest wave is fuelled by AI tools and “딥페이크” (deepfake) technology, which enable images of women—and sometimes even young female classmates—to be manipulated into explicit material with alarming ease. The result: a society already grappling with patriarchal norms, technological excess, and online anonymity facing a new form of gender-based violence virtually indistinguishable from everyday visuals.

The numbers make it clear: help-requests related to digital sex crimes surpassed 10,000 in 2023—setting a new high. And according to a 2024 academic review, Korea’s advanced digital infrastructure ironically becomes a facilitator for these crimes, especially those targeting children and adolescents online. Authorities themselves say the latest spike in cases is being driven by teens both as perpetrators and victims—a signal that “kids doing it to kids” is no longer a fringe phenomenon.

This isn’t just about high-tech mischief. The cultural context is key. South Korea has long been wrestling with gender conflict (“젠더 갈등”) which still looms large, with women’s rights movements advancing only slowly and male-dominant online subcultures (“manosphere” spaces) gaining traction. In this terrain, non-consensual sharing of intimate images—once regarded as “just jokes” or “boys being boys”—is being exposed as violence. It’s no accident that survivors of digital sex crimes in Korea often say they felt powerless, invisible, shamed rather than supported.

In response, the Korean government has been sharpening its tools. Amendments to the law now make mere possession or viewing of sexually explicit deepfake content a criminal offence, with penalties of up to three years in prison or fines reaching 30 million won. Investigations are being stepped up; undercover officers are authorised to act in cases involving adult victims too. But law enforcement alone can’t stop the tsunami; activists warn that the culture enabling such abuses runs deeper.

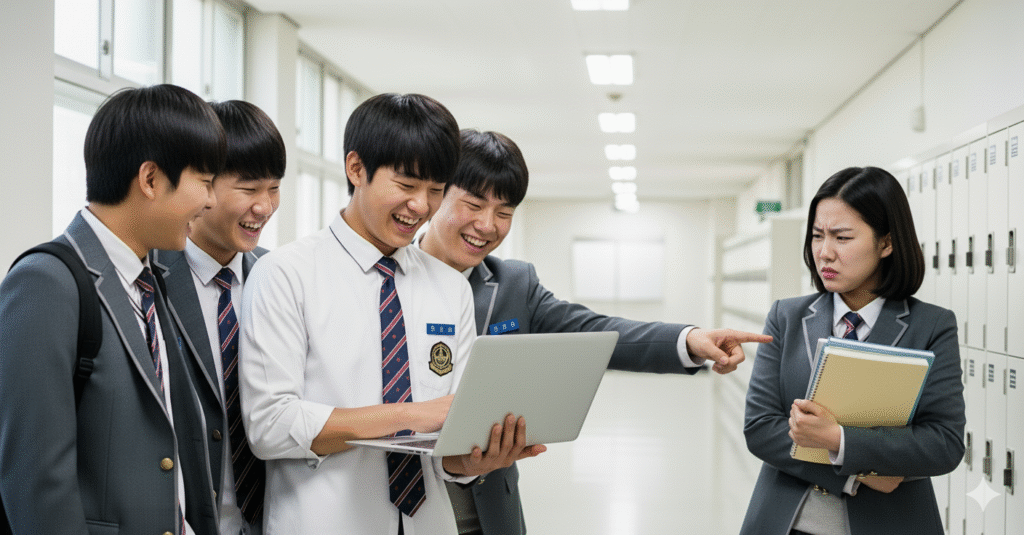

Schools, too, are affected. There are reports of so-called “nudify bots” circulating on apps like Telegram—bots that turn normal photos into sexualised images. Investigations found teens both uploading their own images (often unaware of the downstream risk) and using hacked photos of others. The effect is chilling: “Anyone can be a victim,” said investigators in one 2024 report.

The online arena changes the shape of harm. Unlike physical sex crime, digital sex abuse carries a permanence and scope that defies easy detection—once intimate material goes online, it can propagate globally, outliving the initial incident. In Korean the term “성착취” (sexual exploitation) is now expanding to include “디지털 성범죄” (digital sex crime) and “딥페이크 성착취물” (deepfake sexual exploitation materials). That shift in vocabulary reflects shifting social understanding: what we see is no longer just voyeurism but exploitation writ large.

For survivors, the damage is both psychological and social: shame, isolation, mistrust of technology and peers. For families and schools, the challenge is how to educate teens in a world where cameras and sharing icons are omnipresent. For society, the broader question is whether Korea can overcome entrenched misogyny and a tech culture of anonymity without accountability.

There are glimmers of hope. Civil society groups are mobilising: feminist collectives staged demonstrations; victim-led advocacy groups are calling for more robust removal procedures, quicker law enforcement responses, and comprehensive digital literacy programmes. Some schools have begun teaching “디지털 성폭력 예방” (digital sexual violence prevention) modules. But the momentum must be sustained.

As South Korea hurtles deeper into the digital age, the battle against online sex crimes is not just about policing tech or prosecuting teens—it’s about reshaping the moral economy of how image, consent and gender intersect. When a society’s wired, hyper-connected youth are both targets and agents of online exploitation, prevention can’t be an afterthought. It has to be built into how we educate, legislate and cultivate respect in the virtual realm.

And in Korea’s case, the next chapter may depend on whether the word “디지털 성범죄” (digital sex crimes) triggers collective responsibility rather than quiet shame.

Can we please retire the tired old phrase “boys will be boys”? It’s 2025, not the Joseon Dynasty. Yet every time a teenage boy gets caught making deepfake porn of his classmates, or trading sexualized images like Pokémon cards, someone sighs dramatically and says, “Kids these days… boys just fooling around.” Fooling around? With AI-generated sexual violence? Honey, no. That’s not innocent mischief. That’s cruelty wrapped in code and powered by patriarchy.

Let Auntie tell you something: boys don’t magically wake up one morning with the blueprint for misogyny etched into their sweet, adolescent brains. They learn it. At home. At school. Online. In a culture that gives them infinite digital power but almost zero emotional education. And when they get caught, everyone rushes to protect them—“He’s too young to understand,” “He didn’t mean harm,” “Why ruin his future?” Meanwhile, the girls whose faces were nudified without consent are the ones living with humiliation, anxiety, and fear that their image will resurface every time a classmate scrolls through a Telegram channel.

Parents, hello? Are we awake? You can’t hand your kid a top-tier smartphone, a 5G connection, AI tools, absolute privacy in their rooms, and then act shocked when they discover the darker corners of the internet. Raising children isn’t just about packing lunch boxes and paying tuition. It’s about teaching empathy, boundaries, respect—기본 (gibon), the basics. If your son can run a deepfake generator but can’t understand consent, he’s not “tech-savvy,” he’s uneducated.

And schools—don’t think Auntie forgot about you. Stop hiding behind “we focus on academic excellence.” Excellence in what? Producing emotionally stunted geniuses who can solve calculus but not recognize sexual exploitation? Schools are spending billions on smart classrooms but still treating digital ethics like an optional after-school hobby. Integrate it into the curriculum. Call it what it is: 디지털 성폭력 예방 교육 (digital sexual violence prevention education). Teach it early, teach it often, teach it like their lives—and their classmates’ dignity—depend on it.

Because here’s the truth: when we shrug and say “boys will be boys,” we absolve them of responsibility and rob them of the chance to grow. We keep repeating the same cycle of “harmless pranks” that ruin real lives.

So enough. No more excuses. No more cultural comfort blankets. Boys will be accountable, boys will be educated, boys will be better—if the adults finally do their damn job.