In the neon-lit streets of Hong Kong, where the city hums with the ceaseless clang of trams and the endless drift of queuing crowds, there’s one statistic quietly ruling the headlines: the average Hong Kong woman is now living to 88.4 years, while the average man makes it to just 82.8 years. It’s a gap of nearly six years—what the Cantonese might call a “好大分別” (“hou da fan bit” – a big difference).

At first glance this longevity is cause for celebration. But peel back the layers and you find a more nuanced portrait of society, culture and health behaviour in the city formerly known as a British colony and now a Special Administrative Region struggling with deep-seated social tensions.

The numbers themselves tell the story: according to the Census and Statistics Department, in 2024 women’s life expectancy at birth jumped from 88.1 to 88.4 years, while men’s rose from 82.5 to 82.8 years. Over the decades the trajectory has been upward: since 1971 men’s expectancy rose from just 67.8, and women’s from 75.3. On the global stage, Hong Kong remains perched near the top of longevity rankings.

But why the disparity? Analysts point to behavioural and societal mores: women in Hong Kong typically engage less in high-risk professions or leisure, are more likely to seek medical help earlier, and are more attentive to health checks. Conversely, men are more exposed to hazardous jobs, greater stress (“打工人” lifestyle), higher smoking rates and a cultural reluctance to show vulnerability. Then there’s the cultural dimension: in Cantonese society, the traditional expectation that men carry the financial burden—be the “靠山” (pillar) of the family—brings stress and long working hours, perhaps eroding health reserves over time.

Even the city’s “銀髮經濟” (silver-hair economy) is beginning to reflect this reality. With women living longer, there are more elderly widows, more single-ageing females, more pressure on eldercare services and a shifting social fabric. The city’s healthcare system is already under strain from rising inpatient numbers and the dual burden of ageing plus chronic disease.

Cultural factors add another layer. Hong Kong’s multi-generational living, the importance of “孝” (filial piety), and deep roots in Chinese medicine and preventive culture give women a boost in long-term wellness. Yet at the same time, men may undervalue routine check-ups, scared of being seen as weak or “唔堅強” (“m gin keung” – not strong) in the machismo-tinged social code.

And there’s the longer-term public health picture: although both sexes have gained years, the pace of improvement is uneven. A recent paper in The Lancet Regional Health‑Western Pacific found that females gained about 1.10 years in expected lifespan in 2023, while males gained only 0.60 years. Meaning: the gap is actually widening.

What does this mean for families and society? For a middle-class couple living in the crowded flats around Kowloon or the Mid-Levels, it means wives may outlive husbands by more than half a decade. For urban planners and retirement policy makers it means designing eldercare around the reality that elderly women will dominate the later decades. For younger generations it’s a nudge to rethink questions of health, gender and longevity.

So when you spot an older Hong Kong woman briskly navigating the MTR stations, clutching her reusable tote and sipping herbal tea, she likely embodies decades of good habits, resilience, cultural cushioning and health advantage. Her husband—or male friend of the same era—might have had the same city streets to walk, but perhaps with heavier loads, heavier stress, more cigarettes (“香煙”), later doctor visits. The result: a “長壽差距” (“cheung sou cha kou” – longevity gap) being written into the city’s future.

In a society so focused on wealth, status and outward image, longevity is a quieter victory. But it also raises questions: how will the male side catch up? How will the city adjust to its ageing, feminised elderly demographic? And how will individuals, no matter gender, take agency over their health in a culture that both venerates the elder and punishes the weak?

In Hong Kong, living long and living well are not quite the same thing—and the gender divide remains a telling mirror of culture, class and the choices we make.

Ah, Hong Kong women — the quiet champions of time. Everyone’s talking about how they now live to an average of 88.4 years, but let me tell you, that number doesn’t even begin to capture the story behind it. These women didn’t stumble into longevity by chance. They earned it — one cup of herbal tea, one morning market walk, one unspoken act of resilience at a time.

You see, Auntie has a dearest aunt in Hong Kong — ninety-eight this year, ninety-eight! — with a mind still sharper than the edge of a freshly steamed dumpling knife. When I call her, she still scolds me for not eating enough greens, or for talking too fast. Her secret? “Keep busy, keep kind, and never keep grudges.” She says it in that crisp Cantonese rhythm that makes every phrase sound like a proverb. And she’s right. The women of Hong Kong have made health a lifestyle, not a luxury.

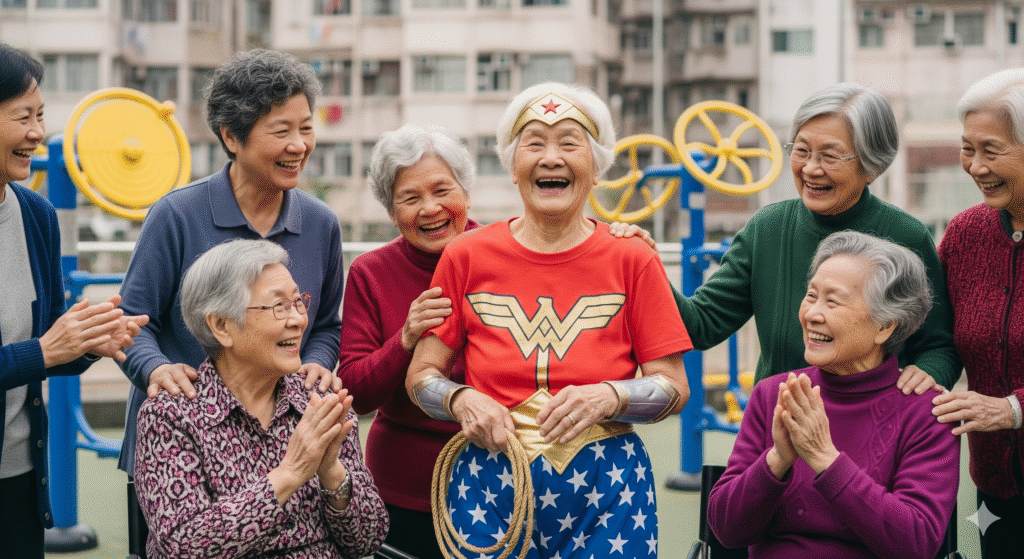

These aunties don’t go to fancy gyms or meditate on mountaintops. They walk everywhere — up the hilly streets of Sheung Wan, through the wet markets of Mong Kok, hauling groceries like they’re lifting kettlebells. They drink soup that could cure heartbreak, sleep early, and worry only about things worth worrying over. They’ve mastered what I call the “Zen of practical living.”

Meanwhile, the men, bless their stressed-out hearts, are still carrying the weight of being the 靠山 (kao saan — family pillar). The long hours, the cigarettes, the reluctance to visit doctors — all noble in the name of pride, but pride doesn’t lower blood pressure.

Hong Kong’s women didn’t just live longer — they outsmarted time. They did it with social ties, laughter, and purpose. They cared for families, built communities, and still found time to nurture themselves, even in a city that runs on caffeine and capitalism. They’ve proven that strength doesn’t always roar — sometimes it just keeps walking briskly, umbrella in hand, to the tram stop.

So when people ask, “What’s the secret to Hong Kong women’s long lives?” Auntie just smiles. Because the secret isn’t a pill, or a diet. It’s attitude. It’s balance. It’s refusing to burn out in a world that glorifies exhaustion.

To my ninety-eight-year-old Auntie, and every Hong Kong woman like her: Salute. You’ve shown us that longevity isn’t just about adding years to life — it’s about adding grace to years.